We

Start Another Century

The

year 1941 marks the Centennial of Prairie Farmer, America's Oldest Farm Paper.

In its pages from 1841 to 1941 may be found the agricultural, social, and economic

history of the middle west.

Settlers were pouring into the prairie country of Indiana and Illinois, into Southern

Michigan and Southern Wisconsinat the end of the 1830's. Some were artisans, merchants

and traders, but most of them were farmers. Along the Wilderness Road to Cumberland

Gap, through the Blue Grass Country of Kentucky they came, crossed the Ohio River,

moved into Indiana. Some forded the Wabash at Vincennes, and came into Illinois.

Over the old timber-bedded Michigan Road they moved northward across Indiana to

the foot of Lake Michigan, meeting other streams of prairie schooners that had

come west.

These settlers had known no farm land like the prairies. They could guess the

land must be fertile, since the grass grew luxuriantly, but there was no experience,

no equipment for farming such land. Grass roots made a mat a foot and a half deep.

Crude plows would not turn this primeval turf.

Stray cattle roamed everywhere, a menace to the pitiful hand-planted fields of

grain. Wild hogs, coyotes, the sweeping wind, the myriadsof green-head flies that

would kill a horse, put a test on the stoutest hearts. Malaria and the "shakes"

came from clouds of mosquitoes on stagnant water. Rattlesnakes seemed everywhere

underfoot. And when a prairie fire came over the horizon with the speed of the

wind, it seemed as if the end of the world had come.

The prairie pioneers had to forget all they had known of farming back east, and

learn anew how to farm on the prairies.

There was no experiment station bulletin for reference.

There was no publication that understood their problems.

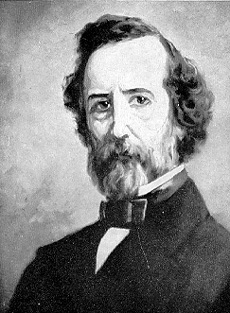

So it was that one hundred years ago, in 1841, John S. Wright, a man of extraordinary

vision and understanding and zeal, led a progressive group of men in founding

an agricultural society and establishing a paper that should serve the farms of

the prairies.

That paper was Prairie Farmer, now a century old.

Through a century of service, Prairie Farmer has worked shoulder to shoulder with

farmers as these prairies have become the most fertile in the world.

It has seen the bent backs of men straightened as one new machine after another

has lifted the load.

Prairie Farmer has watched as the rutted trails of those days have changed to

thousands of miles of modern paved highway. It helped to promote the building

of railroads.

When pioneer children had little or no school facilities, the sturdy young publication

fought for a new and untried idea, free schools and universal education for every

child.

It was still young when that strange new invention, the telegraph, began to bring

messages by "lightening," and the first telegraph office in Chicago

adjoined the office of Prairie Farmer, in 1848.

Such an idea as a college of agriculture, or an experiment station was utterly

remote, until in 1852 a letter to the editor of Prairie Farmer suggested the idea.

Steadfast work and campaigning brought the establishment of such schools by a

federal law signed ten years laterm in 1862. It was signed by one who had reason

to know the need for such education, one who knew Prairie Farmer, the Prairie

President, Abraham Lincoln.

New crops, improved live stock, new economic conditions came. Cities, lifted on

the broad shoulders of a powerful agricultural area, grew great. Agriculture came

of age.

With reverence, we of Prairie Farmer turn the pages of a hundred annual volumes

in which this amazing story is told. We read how Prairie Farmer made the first

attempt to harness radio for farm service, when messages were still ticked out

in dots and dashes.

Then came WLS, seventeen years old in 1941, made a part of Prairie Farmer service,

using most modern equipment and methods,but dedicated to century-old ideals.

May we of Prairie Farmer-WLS who carry on into the new century, serve agriculture

as truly and well as those who charted the first hundred years.