|

Of

television's total output, a scant five percent originates in Chicago. But it

surpasses others for ingenuity, charm and distinctive showmanship.

In Chicago,

bless their integrity, they're copying neither the New York stage not the Hollywood

cinema. They're evolving an art form that is peculiarly television's own. They

started with no great names and no great budgets, either. Theirs was the desperation

of the shoestring summer stock company, 'What you ain't got, improvise!'

Chicago improvised first with the cameras. This was the boldest stroke of all.

And the best camera you're likely to see on video today is, more often than not,

on a Chicago show. Out there in the city Carl Sandburg called 'hog-butcher for

the world' they use a TV camera the way an artist uses a brush. It is not simply

a cold piece of mechanical machinery, a device for recording the movement. It

comes alive. It surveys the goings-on with sly winks, with wide-eyed surprise,

and with trembling awareness of the beauty that lurks in shadows as well as the

beauty that dances in light.

They don't anchor cameras to fixed spots on the floor, as happens on many New

York shows. They roam at will, these Chicago cameras. They glide, they spring,

they swoop. And you, the viewer, get a view of the show that transcends description.

Do you wonder that people in the trade say the Chicago touch is to television

what the French touch is to cooking. It's that je ne sais quoi, that zest

plus. You can't define it, but oh what a pleasure to savor it.

Fred Allen reportedly attributes his rather spectacular failure in television

last fall to the fact that he didn't obey his impulse to do his show from Chicago.

'They ought to tear down Radio City, rebuild it in Chicago and call it 'Television

Town', says he.

| Right:

Kukla and Ollie |

|

What are these shows,

marked with the unmistakable Chicago touch? Well, the first one that comes to

mind is Kukla, Fran and Ollie. This is a puppet show, without strings,

and with one outrageously talented young man, Burr

Tillstrom, providing ten different voices for the little characters he 'wears'

like long-sleeved gloves. Only one 'live' person is seen and she is Fran Allison.

Fran stands beside the Kuklapolitan stage and converses with Oliver Dragon, Mme.

Ooglepuss, Fletcher Rabbit and the other puppet folk. We know that she believes

implicitly in them as people. Consequently you follow suit.

Now in their fourth year on television, Kukla and Ollie are so well known to some

children as their brothers and sisters. Each puppet has a distinct personality.

And you feel quite sure that each one has a busy little life of his own away from

the program. Fletcher collects guppies and starches his long ears (one of which

twitches when he's excited). Ollie likes to pore over such books as 10,000

Things a Boy Can Build. Mme. Ooglepuss, a lady who wishes she might have been

an opera star, practices her scales and plans little musicals. Beulah Witch, a

frowsy, shrill little character whose broom is equipped with radar, undoubtedly

lives alone in a Charles Addams garret and cooks her wicked brews over a Sterno

can.

Though it has been

called a children's program, Kukla and Ollie is, in some ways, highly sophisticated.

On what other show would you meet a dragon who casually mentioned that he had

to take care of his one tooth because it was 'prehensile, you know'?

Fan letters to

Kukla and Ollie frequently run between six and eight thousand a week. The puppets

have a tremendous wardrobe, much of it sent in by viewers who just can't resist

knitting a little sweater for Kukla or stitching up a mink cape for Mme. Ooglepuss.

Tillstrom, a slim boyish chap in his early 30's earns $10,000 a week, has more

sponsor offers than he can accommodate. The show is seen five nights a week, 7

to 7:30 p.m. in the East. Some of its faithful fans, such as Tallulah Bankhead,

never leave the house or even eat dinner 'til the Kuklapolitans are off the air.

| Right:

Dave Garroway |

|

Garroway

at Large

is a half hour Sunday night variety show. It is the essence of quiet, relaxed

entertainment. The camera work is unparalleled. And there is no studio audience.

'Television is an intrinsically personal medium', says the spectacled, six-foot-plus

Garroway. 'It is a good deal more personal than radio, simply because when you

watch somebody perform in your living room you feel much closer to him than when

you hear him'.

And since the average number watching any set is only three or four, he continues,

it follows that a performer should aim his stuff not at several hundred people

in the studio but at that small intimate group in the darkened living room.

'To me,' says Garroway, whose Navy induction tests showed he had a near-genius

I.Q., 'this means that television may very well change the whole character of

American humor.'

That small group, reasons Garroway, and by extension, the whole Chicago school

of television, doesn't want to see pies thrown in the face. They want the 'small

laugh,' the quiet chuckle, the inner glow. And this is what Chicago gives them.

Garroway has his own permanent stock company: three excellent singers, a comic

sidekick and some fine dancers. The music is unusually fine. And the 'effects,'

lighting, sets, odd props, are always imaginative.

Garroway himself is merely the host. He ambles casually over the immense TV stage,

the cameras following him with that special Chicago lope. He narrates the musical

pantomimes, he introduces the various numbers, he chats agreeably about the linoleum

his sponsor makes. Nobody on the Garroway show ever 'punches,' nobody ever talks

down to the folks at home. These are pleasant, gentle people. And they've keyed

their show to the ideal mood for late Sunday evening, 10 p.m. EDT, NBC. Of its

kind, comedy-variety, the Garroway show is far and away the best in television.

It makes Milton Berle and his brethren absolutely unbearable.

|

Right:

Chet Roble, Beverly Younger, Studs Terkel

|

|

A dramatic show without

a script is Studs' Place, on

view Saturdays, 5:30 p.m. over ABC. The actors are given a rough outline of the

story at rehearsal. They improvise their lines as they go along. And if everyone

seems perfectly at home in his part, there's a reason for it. Studs Terkel, the

proprietor of this mythical tavern, plays himself. And he grew up in a restaurant

operated by his family. The part of Phil Lord, an eccentric old-time actor is

played by Phil Lord, in real life an eccentric, old-time actor. Chet Roble, the

jazz pianist, plays himself, as does Win Stracke, a guitar player and folk singer.

Charlie Andrews,

the clever young man who writes Garroway's continuity, supplies the story outlines

for Studs' Place. Andrews, plus a producer named Ted Mills, plus a director

named Bill Hobin, who's only 26, comprise the Big Three of Chicago television.

Andrews recently set down on paper his philosophy of the 'Chicago School'.

'Unlike theatre-variety thinkers in New York, we could not build a show merely

by getting some big names and putting them in front of the camera,' he explains.

'We were virtually forced to find quality in the pan of a camera, the trick of

a design, and perhaps most important, careful attention to the show's conception.'

Result of this thinking, Andrews says, is that everyone involved in the show becomes

a creative contributor to the program, everybody from the 'producer down to the

dolly pusher.'

In Chicago,

moreover, pains are taken to see that the total show is more important than the

performers. Old technique of getting a big name and building a show around him

had to be abandoned because Chicago had no big names. 'The Chicago group built

the show first, then cast it,' Andrews goes on to say, 'treating musical and variety

shows exactly as they would variety shows.'

Technical equipment came, out of this same necessity, to be regarded as instruments

of creative art. It was a kind of compensation. The camera was given complete

freedom of movement. It ceased to be a mere reporter of the event. 'Where the

camera can swing around a 360 degree arc, cameramen and directors come into their

own creatively,' Andrews believes. 'They are no longer mere technicians, as they

tend to be in theatre television shows, pointing their cameras at something someone

else has created. In a studio, a director like Garroway's Bill Hobin can create

something...'

Another great

Chicago show, though entirely different from the usual studio production, is Zoo

Parade. This Sunday afternoon visit to the animal kingdom is presided

over by Marlin Perkins, director of the Lincoln Park Zoo. With the air of a man

showing you his Rembrandts and Renoirs, Mr. Perkins makes you acquainted with

his monkeys, snakes, bears and birds. So earnest is he in showing you the animals

that he recently received a severe snakebite, just before air-time, and spent

the next two weeks in the hospital.

In Zoo Parade the cameras are just as wondrous in their workings. You see

the animals as close as possible, and always you remark how healthy and clean

they look, how content in their public lodging house. Mr. Perkins' love for his

charges has a St. Francis quality, and I'm not saying that lightly. You should

see the chimpanzees hug him!

Zoo Parade this year won one of the coveted Peabody Awards, the only award

in radio and television that carries any prestige. The others are handed out casually,

more as promotion stunts for the donors than tokens of merit for the winners.

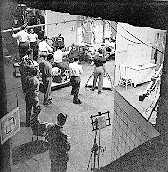

| Left: The

Hawkins Falls set |

|

| Curator's

note: This photo was taken when 'Hawkins Falls' was produced on the

stage of Chicago's Studebaker Theater. NBC leased this facility during the period

the Merchandise Mart studios were incapable of handling the daily production load.

In the foreground you see the back of announcer Hugh Downs' head] |

Chicago pioneered

in the radio daytime serial. And it has recently given a fairly good one to video.

Title is Hawkins Falls, Pop. 6200.

The plot is sudsy, to be sure. But there is some first-rate acting, particularly

by Bernadine Flynn. Radio listeners will remember Miss Flynn from a show called

Vic 'n Sade. She ws Sade.

|

Right:

Bernadine Flynn and Phil Lord

|

|

|

Left: Ben

Parks, 'Hawkins Falls' director |

Two other Chicago

shows deserving mention are Super

Circus and Acrobat Ranch, both for kiddies. There's also a science

demonstration for children on Saturday afternoons called Mr. Wizard. Once

again, it's the best of its kind. Informative, but fun to watch.

All in all, Chicago has the ingenuity, the daring and the taste that will save

television from the terrible fate that's been Hollywood's. If the day ever comes

when television establishes a true 'academy', a place where the young and hopeful

may go to learn the art of television programming, Chicago is the only conceivable

place for such an institution.

|